World News

Jury Selection for Parkland Shooter’s Sentencing Trial Begins

-

General News3 days ago

General News3 days agoKenya Police Recruitment Training: Complete Preparation Guide

-

General News1 week ago

General News1 week agoMagoya Boils! CS’s Choice Moses Omondi Cornered by Angry Ugunja Youths

-

General News1 week ago

General News1 week agoHow the Government Sank Sh49.5 Billion Into Housing Projects Without Land Ownership

-

General News1 week ago

General News1 week agoFrom Ivory to Rhino Horn: How Feisal Mohamed Ali Keeps Escaping Justice

-

General News7 days ago

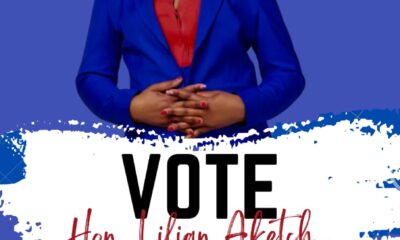

General News7 days agoA New Hope in Ugunja: Lillyanne Aketch’s campaign is shaking up the by-election.

-

General News3 days ago

General News3 days agoRyan Injendi Hits Out at Mudavadi Over Malava UDA Nominations

-

General News6 days ago

General News6 days agoGithunguri MP Gathoni Wamuchomba Denies Claims of Spying for UDA

-

General News3 days ago

General News3 days agoWhat to Do If You Are Unfairly Disqualified from Police Recruitment in Kenya